Research Priorities Should Depend on the Future Demand for Technology

On February 8, we celebrated Russian Science Day. The recently released report entitled, ‘Russian Science in Figures’, compiled by HSE’s Institute for Statistical Studies and Economics of Knowledge, details the current state of science funding, the percentage of the population in scientific jobs, and scientific research. Leonid Gokhberg, director of ISSEK and the first vice-rector of HSE, told us more about it.

What do Russian Scientists Write About?

Over the last few years, the number of publications by Russian scientists in international journals has increased at a faster pace than in many other countries. In fact, in 2016, Russia came 14th in the world publication ranking. However, Russia is held back somewhat by problems with structural indicators, for example, with citations, which remain low. About a third of articles published by Russian scientists are in co-authorship with foreign colleagues. This is, of course, a good thing, because it demonstrates strong international scientific cooperation. However, in highly-cited publications, the percentage of articles with foreign co-authorship is as large as 90%, and this indicates the insufficient strength of our Russian authors' potential.

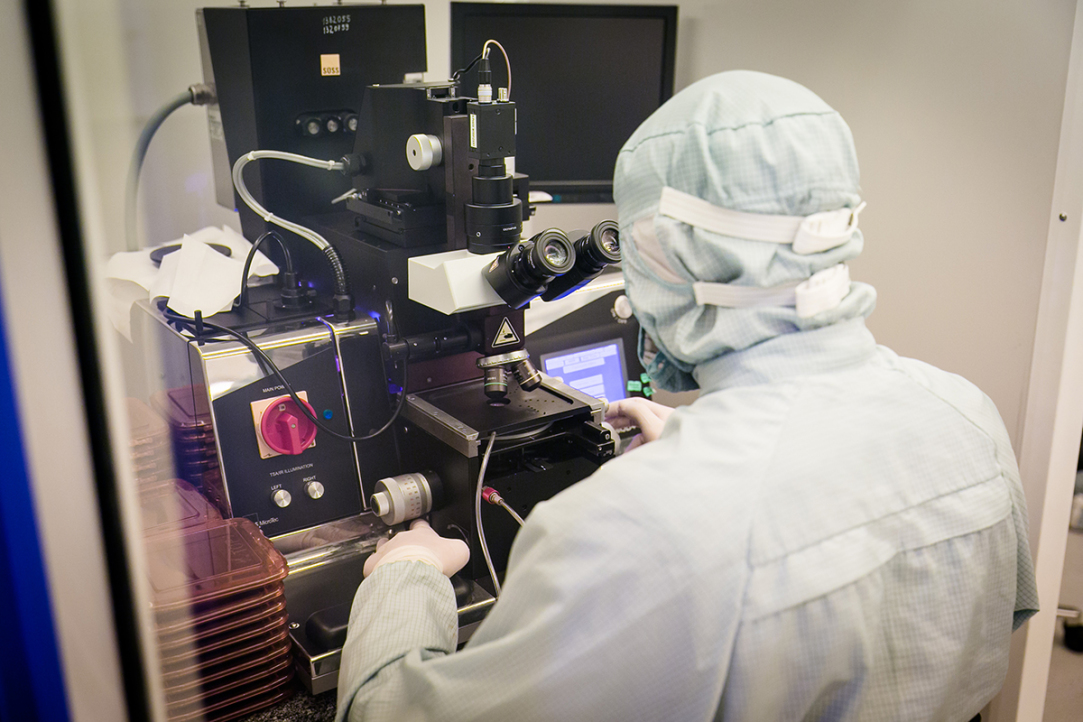

Russian research follows the tradition of Soviet science. In comparison with the rest of the world, a large number of articles are published in fields of science which were major foci under the Soviet Union, and where significant progress was made, which was able to be preserved. This includes physics, space exploration, mathematics, chemistry, materials science and Earth science. Unfortunately, we failed to harness the research potential of the most dynamic areas, which are now on the crest of a new technological wave. This includes the life sciences (e.g. biology, medicine), and cognitive and computer sciences. Social sciences also come into this, as they are converging more and more with the natural sciences.

Where is Russian Innovation Headed?

Continuous monitoring and evaluation of the quality and effectiveness of scientific research is very important, and such an assessment should take into account the most important factors, that is, socio-economic, global scientific and technological trends, as well as market demand. This should be the benchmark for setting priorities. This is certainly the case with applied science- it should reflect the future demand for technology. And, even in the more traditional areas of Russian research, it is important to evaluate its structure more carefully: to what extent do these or other research foci correspond to prospective trends? It may be necessary to prioritize those where there is a real potential to make headway, that is, potential for real development.

The Russian population tends to be very positive about science and technological progress – even more so than people in many Western European countries

Over the last five years, Russia has moved from 62nd place to 45th in the global innovation index (GII). However, in terms of ‘influence of innovation’ – an important GII indicator - Russia doesn’t even make the top hundred. This indicator is related to the scale of production in high-tech industries, such as aircraft construction, the space sector, instrumentation, medical equipment, electronics and telecommunications. Compared to the existing oil and gas component of the economy, and the very high percentage of trade and other service industries, these high-tech industries make up a very modest share of the economy.

Are There Enough Resources for Russian Science?

In terms of government budget funding allocated to science, Russia is among the top ten in the world, ahead of countries such as Great Britain and Italy, and is almost on the same level as France. However, in these countries, in contrast to Russia, the lion's share of science spending is done by companies. The same is true for science spending in terms of the GDP- Russia is only ranked in the top thirty. Clearly, science is not a priority for economic agents in Russia.

Business financing in Russian science has been decreasing over the last few years, and it is now at more or less the same level as it was in the second half of the 1990s, when the state dominated the market for scientific research. This does not mean that the state should reduce spending on science - on the contrary, it should increase it, however it should be guided by the level of research and its quality. There should be no funding of ‘second class’ research. In terms of applied research, in the civil sector, the state should act as a financial ‘catalyst’ when it invests in research, which will then be picked up by the business. Alternatively, the government could offer non-monetary incentives, creating an institutional environment and infrastructure, such that businesses invest science more heavily.

Where Does Russia Find its Scientists?

The Russian population tends to be very positive about science and technological progress – even more so than people in many Western European countries. This is intensified by the traditionally high level of education and culture of Russia’s population. However, the degree of awareness of the latest achievements of science and technology in Russia is extremely low - only about 10% of the population consider themselves to be well-informed. This is one of the lowest percentages in Europe. This is the case because, for one, Russian scientists rarely get excited about breakthrough achievements of global significance and aren’t able to ‘sell’ them to the rest of the world. Furthermore, mass media, which the population tends to tune into, does not give a lot of airtime to the world of science.

Despite the positive attitude towards science, only 32% of Russians surveyed say that they would be happy if their child chose a scientific career. This is much lower than in developed countries. The Russian population is very aware of the salary level in science, as compared to other sectors. The salary of a scientist is one and a half times higher than the average salary, however this is still not enough to ignite the interest of young people in a scientific career.

In addition, the training of scientists specifically focused on science in Russia occurs on a very small scale. It has a ‘niche’ quality. The percentage of university graduates accepted into research positions has decreased by half over the past twenty years – up to 0.6%. Furthermore, the percentage of people in scientific professions generally has begun to decline. However, recent data show that universities are enhancing their presence in science - in terms of personnel, hiring of young people into scientific positions, publications and patent activity. According to these indicators, university science is ahead of other sectors. But: it takes time for universities to accumulate a ‘critical mass’ in order to have a decisive influence on the development of science as a whole.

Russian Science in Figures, 2018

See also:

The Higher School of Economics Proposes Measures to Unlock the Potential of Science in Russian Universities

Speaking at the Professor’s Forum on February 7, Yaroslav Kuzminov, Rector of the Higher School of Economics, noted that science in Russia, especially in Russian universities, is underfunded, and suggested several steps to support Russian researchers and help them reach their full potential.

Russian Science, An Insider’s View

February 8th is Russian Science Day. How do people, directly involved in the process of generating and advancing new knowledge - scientists, entrepreneurs and public servants - assess the health and potential of Russian science today? Here are the results of a survey by HSE researchers in which experts, representatives of government bodies, scientific organisations, universities, hi-tech companies and social organisations express their views on the state of science in Russia and what should be done to improve it.