Digitized Archives Are a Great Treasure

Digital archives and electronic versions of manuscripts are essential to the work of modern-day philologists, linguists, and literary scholars. The possibilities that digitization opens up to researchers were the focus of the second international conference of early career researchers of Russian literature. The conference had the theme of ‘Text as DATA: The Manuscript in the Digital Space’ and was hosted by the HSE Faculty of Humanities.

The conference was dedicated to the memory of the late Nikolai Bogomolov—a literary scholar and the foremost authority on textual studies of the Silver Age of Russian Poetry. The event took place on May 25.

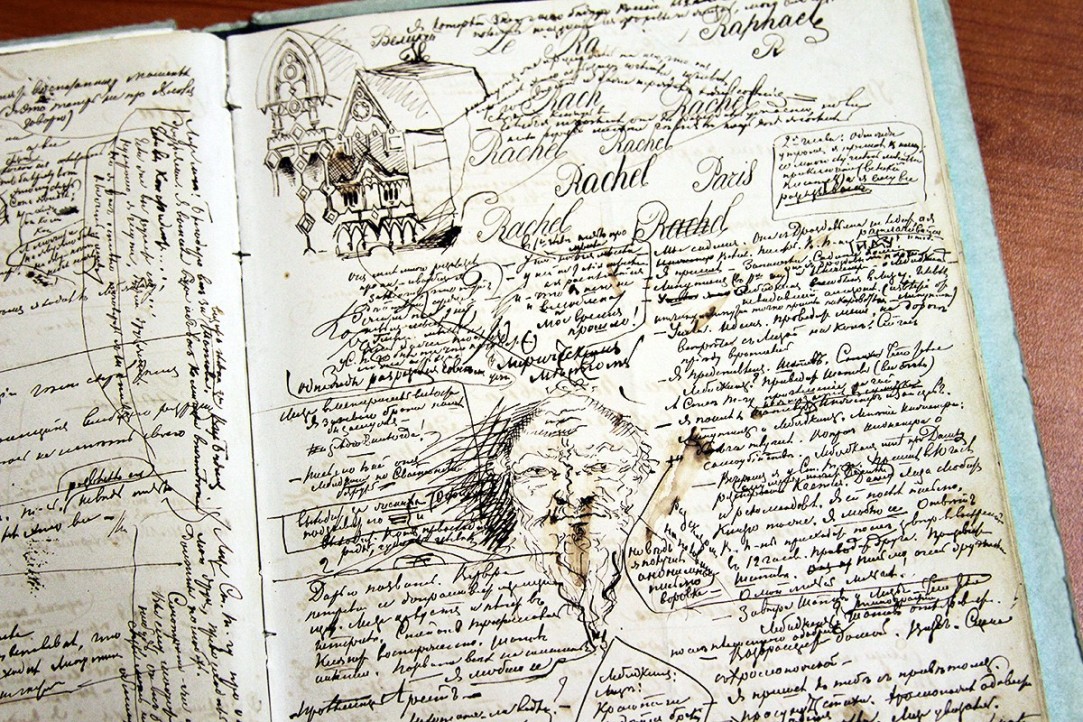

In the early 1960s, Mikhail Bakhtin called the text ‘the primeval given’ of humanities. Nowadays, a literary text can be viewed as a dynamic information array—a digital form of manuscript. This is how the organizers unwrapped the theme of the conference. In their presentations on the handwritten legacy of 20th century Russian literature, young scholars— the main participants of the conference—spoke about the possibilities that digitization of archives offers and the search for new methods and approaches in textual studies.

The event was hosted by Elena Penskaya, Chair of the Steering Committee and Professor of the HSE School of Philological Studies, and Daria Moskovskaya, Chief Research Fellow and Head of the Manuscripts Department at the Gorky Institute of World Literature with the Russian Academy of Sciences.

‘The lockdown made us all realize how important it is to keep in touch with the archives, to work with manuscripts,’ says Elena Penskaya. ‘Digitized archives mean open access for all researchers. They are a great help.’ To quote Rita Giuliani of Sapienza University (Rome), ‘we all know how one can make honest mistakes when deciphering some word or other, so digitized archives are a great treasure.’ Evgeny Kazartsev, Head of the HSE School of Philological Studies, called the ability to reproduce literary texts the highest manifestation of human intelligence.

These are complex matters and complex texts we work with, and ways to faithfully represent these complex meanings in digital form are yet to be found

These were the words that Elena Penskaya used to back up her peers’ message. Daria Moskovskaya added that digitizing manuscripts is more than just converting a hard copy to a soft copy. We are on the verge of a new reality and new possibilities, whose essence has yet to be fully discovered. Catriona Kelly of the Oxford University added that institutionalization is impossible unless there is a digitized archive.

Even though we still retain the centuries-long connection of thoughts, fingers and pencils, digitization of texts is necessary and inevitable, believes Jörg Schulte of the University of Cologne. Fyokla Tolstaya, a journalist and a TV presenter, pointed out that today’s agenda should focus on communication among the digital systems of various projects and various archives; what we need is horizontal linking.

At the plenary session, young scholars presented their research and talked about their experiences with archives, manuscripts, and autographs. All of them paid tribute to the late Nikolai Bogomolov. As Rita Giuliani said, without him, science has become poorer.

Aleksei Kozlov of Novosibirsk State Pedagogical University (NSPU), as his peers agree, put a unique twist on the topic of his presentation: ‘The archive in the post-Gutenberg era: supply and demand.’ He talked about the sociological aspect of archive digitizing.

Transforming an archive into electronic form puts it within reach of great many readers, including those living in far-flung regions. This puts the country’s centre and its outposts on an equal footing

This is crucial, believes Aleksei Kozlov.

Vlada Gaiduk, HSE University, spoke about the work of publishing the diaries of Valery Bryusov. They had started this project together with Nikolai Bogomolov. To date, there hasn't been a complete edition of the poet's diaries or his biographical notes. This is largely due to how difficult his manuscripts are to transcribe—author's edits and shorthand abound, hence there is a multitude of curly brackets and question marks in the printed editions of such material. An electronic version, however, can be magnified to untangle the details of even the most convoluted handwriting.

Since the beginning of last year, HSE students have had access to ‘Autograph. 20th Century’, a web portal that publishes electronic copies of manuscripts of Russian writers. There is a web service called Textographer for decrypting manuscripts. The system works with handwritten as well as typewritten and printed sources. It enables such subtle actions as teasing apart layers of edits and comparing different versions.

Anna Krasnikova, the Catholic University of Milan, faced a challenge no less daunting while working with Vasily Grossman's archives. According to Anna, even now it’s impossible to say which writings of Vasily Grossman can be considered critically established. She also spoke about the state of textual studies on the subject. The challenge here is also that ‘everything is intermingled’: the manuscript of the novel Life and Fate was seized, its fragments were later published here and there, then there was a samizdat edition. Anna said that Textographer facilitates the task of transcribing manuscripts by enabling semi-automatic versioning, editing and cross-referencing.

Marina Kudryashova and Olga Ermakova, HSE University, are working with Mikhail Sholokhov's legacy. His archive has been digitized and published online at ‘Autograph. 20th Century’. Presentations were also given by Anfisa Savina of the Gorky Institute of World Literature—‘World Literature: a Calendar of Events (based on the ego documents of Alexander Blok and Korney Chukovsky)’, and Mikhail Saprykin of MSU—‘Manuscript in .doc format: problems of textual scholarship in the computer era as illustrated by some unpublished articles by Vsevolod Nekrasov.’

The conference had four sections in addition to the plenary session. Presentations in the Manuscripts and Institutes section included ‘The First Theatre Agency for Russia and Beyond and the repertoire of European cabarets in the 1910s’, ‘Moscow Art Theater II: A stage reading of Isaac Babel’s Sunset through the lens of archival materials, and others. The second section, entitled Poetics of Letterforms, discussed topics such as ‘Poetics of letterforms as poetry: The significance of visual and illustrative components in the writings of Velimir Khlebnikov’ and ‘Vladimir Mayakovsky’s work on poster captions (based on notebooks)’. The third section, Theater Archive, discussed topics such as ‘On the origins and reconstruction of Alexander Tairov’s production of The Threepenny Opera by Bertolt Brecht (Kamerny Theater, 1930)’ and ‘Recreating the history of production and conception of Boris Godunov at the Taganka Theatre, based on factual and analytical sources’. Finally, presentations in the fourth section, Women's Handwriting, covered topics such as ‘The problem of women's letters: on Simonov's Trip from the archives of Aleksey Tolstoy’, ‘Thank you for your letter’: the status of the letter in the archives of the philologist (based on Lidiya Ginzburg’s letters to Vadim Baevsky)’ and others.