Quality of Life or Medicine? HSE Researchers Learn the Key to Living Longer

Everyday living conditions — income, housing, and sanitation — affect health and life expectancy more than the availability and quality of medicine. At the same time, the health system itself plays a crucial role in treating infection. This is what a recent study by researchers of HSE University has found.

In the webinar series, ‘Economics and Data: Opportunities for Health Care’, Professor Marina Kolosnitsyna of the Department of Applied Economics of HSE University, presented a report entitled ‘The Contribution of Individual Factors to Public Health’. The research team also included Tatiana Kossova, Maria Sheluntcova and Ludmila Zasimova.

Marina Kolosnitsyna noted that health is influenced by many factors, such as heredity, quality of environment, nature of employment, socio-economic factors, and the demand for health services, all of which are interrelated. Health becomes part of an individual’s human capital which can be increased by investing in recreation, sports, improved living conditions, and medical services, and it can be decreased by negative investments: alcohol consumption, tobacco, and inactive lifestyles.

Thus, a population’s level of education and a certain level of income create a demand for health care services, turning it into an economic sector, which in turn affects the quality of life and life expectancy.

The factors having a negative effect on the health of a population and mortality rate differ significantly depending on a country’s well-being and economic development. In developing and underdeveloped countries, key causes of shortened life expectancy and high mortality are malnutrition, poor housing and sanitation standards, low income, and high crime rates, while in developed countries, the key causes are physical inactivity, obesity, stress, and alcohol consumption.

The report assesses the quantitative contribution of select factors to the health of a population. Marina Kolosnitsyna believes that incidence rate is not a good indicator, as it reflects not the state of a population’s health, but rather the number of visits to health care facilities, which is higher in big cities and lower in the countryside, where access to health care is difficult. In this respect, the researcher used life expectancy, which considers mortality rates at different ages and from specific diseases. Studying mortality rates also allowed the researchers to perform international comparisons.

Life expectancy in high-income countries is significantly higher than in low-income countries. In particular, in 2015, the average life expectancy was 82 years in developed countries and 69 years in developing countries. Improvements in quality of life and health care resulting from increased income in developing countries are, however, more pronounced than those in developed countries. It is easier to improve life expectancy from 50 to 60 years than from 70 to 80 years, explained Marina Kolosnitsyna.

GDP per capita has the greatest impact on increasing life expectancy globally, followed by health expenditure, animal protein consumption, and the proportion of the population living in an urban setting

In the group of countries with medium life expectancy (68-77 years), which includes Russia, the key factors are the proportion of the population living in an urban setting, health care costs per capita, and GDP per capita, while the quality of nutrition plays a lesser role.

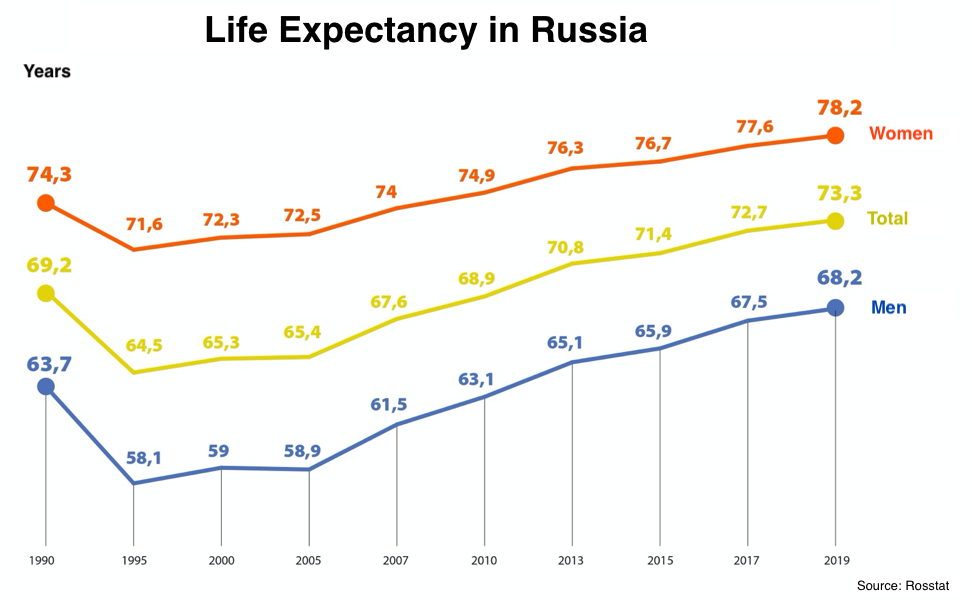

Marina Kolosnitsyna notes that with current resources, Russia could have a higher life expectancy rate than its current average of 72.9 years recorded in 2019. There are many countries that rank lower than Russia both in terms of GDP per capita and health care spending per capita, such as Iran, Armenia, Colombia, Serbia, and Vietnam. However, life expectancy in these countries is higher than in Russia: 76.4, 74.9, 77.4, 75.9, and 75.3 years, respectively.

To compare factors that influence life expectancy in certain regions of Russia, Marina Kolosnitsyna used Rosstat (Federal State Statistic Service) data for 2005-2016 across 77 regions of Russia. The Crimea and Sevastopol were excluded from the list, as they only became part of Russia in 2014, as were select regions with incomplete statistics (Ingushetia, Dagestan, and Chechnya). However, as noted by the author of the report, per capita income, rather than per capita GRP, was used as the key indicator of well-being.

Professor Kolosnitsyna noted that, all other factors being equal, socio-economic aspects play a key role in reducing overall mortality and increasing life expectancy: the quality and size of housing, average per capita income, and crime rates. Health care quality and lifestyle, including alcohol consumption, have less of an affect. The effects of climate and natural conditions, as well as emissions to the atmosphere, are relatively minor: in fact, in warm regions, people are less sick and, on average, live longer. But when this variable is included in a model where there are many other factors, it ceases to be relevant, the HSE University professor explains.

According to Marina Kolosnitsyna, life expectancy in the North Caucasus is high compared to the central regions of Russia, due in part to low alcohol consumption and possible underreporting of income.

She also noted that this was not the case when calculating the impact of similar factors on mortality from infectious diseases. Systemic health care indicators, such as the number of hospital beds, doctors per capita, the burden on health workers and facilities, and the availability of health care, are key factors in reducing or, conversely, increasing mortality from infectious and parasitic diseases.

This, according to Marina Kolosnitsyna, should influence the distribution of funds in different health care sectors during the pandemic, when coronavirus outbreaks have once again become acute.

The coronavirus pandemic could increase the role of the availability and quality of medicine in public health and life expectancy, she said. However, conclusions can be drawn later, probably in a year’s time, when regional life expectancy data that have been updated to reflect current mortality rates, related health care network indicators, and other figures (particularly income) are published.